Bullet time

Kathryn Bigelow shoots and does not miss with A House of Dynamite

“The history of civilisation is largely the history of weapons,” wrote the great George Orwell in his 1945 essay, You and the Atomic Bomb. In particular, he noted that a supremely powerful weapon controlled by a handful of superstates was “Inherently tyrannical,” reminding readers of HG Wells’ long-held belief that we would be the authors of our own destruction.

Born late in 1978, I was a child of the ‘80s, the opening half of which witnessed a sabre-rattling resuscitation of the Cold War, at least partly inflamed by the hawkish stance of Reagan and Thatcher against a détente with the far from blameless Soviet Union.

Fear of “the bomb” was instilled in me from a very early age. Not least because I watched Barry Hines and Mick Jackson’s devastating in every sense docudrama Threads and the Watership Down-level trauma of When the Wind Blows, Jimmy Murakami’s animated adaptation of Raymond Briggs’ haunting graphic novel, while far too young.

The older I got, the more I fed my paranoia, reading extensively about the ticking Doomsday Clock while listening to the spectral invocation of Morrissey’s Everyday Is Like Sunday and obsessively watching Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove.

No, I did not learn to love the bomb.

I remain as sure as ever that there is no moral defence for bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In so slaughtering innocent civilians, lest we ever remember, a rift in the natural order was forced open. An infernal crack that, if David Lynch’s return to Twin Peaks is to be believed, allowed the likes of Bob to crawl through.

Annihilation wasn’t merely speculative. I grew up in the shadow of the UK’s submarine-based nuclear ‘deterrent’, Trident, based at Faslane, less than an hour’s drive from Glasgow. Now, in the hypothetical hour of our mutually assured destruction, I would have to watch from Melbourne, Australia, as my family and friends burned.

How long would I have? Nevil Shute’s 1957 novel On the Beach posits only a few months before fatal fallout drifts its way south. Long before the ghostly sight of an abandoned Picadilly Circus dropped jaws in 28 Days Later, the empty steps of Victoria’s parliament shivered spines as Hollywood’s finest – Ava Gardner, Gregory Peck, Fred Astaiar and Anthony Perkins – came to Frankston for Stanley Kramer’s 1959 adaptation.

Come, Armageddon! Come!

The beach offers one of the few calming moments in the mighty Kathryn Bigelow’s ferociously anxiety-inducing A House of Dynamite. A fighter jet pilot, as yet unaware of his soon-to-be-leading role in history’s downfall, is adrift in the ocean, dog tags dipped.

A ripple in the surface of things captured by Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker cinematographer Barry Ackroyd, this blissful beat opens the second of three concentric chapters, each of which radiates out from the inescapable blast zone of one awful truth:

We are our own worst enemy, and this is my worst nightmare.

Working from an electric screenplay by Zero Day scribe and former NBC News president Noah Oppenheim, a man whose surname takes us more than halfway to death, the destroyer of worlds, Bigelow allows us multiple angles on the US government’s panicked response to a possible nuclear strike of unknown origin.

With a dizzying array of actors at her command, Bigelow adroitly navigates this many-headed beast. Caught as if on the hop with a handheld freneticism by Ackroyd, we bob and weave through a sea of rictus-seized faces, along the chain of command.

In their collective company, just another morning is thrust into judgement day. Juggling duty, never more immediate, with their humanity, if this is the end, they keenly realise they will die, or worse, survive without their loved ones.

Opening on the frosty scrabble of windswept Alaska, Major Daniel Gonzalez (Anthony Ramos) is hung up on by his unimpressed partner. Returning to his command bunker just in time for his camouflage-clad team to spy the bogey, at first, they assume it’s just another failed North Korean test or similar. But when it drops to suborbital, a statistical list of target cities firming by the minute, DEFCON blinks red like HAL 9000’s eye.

White House down

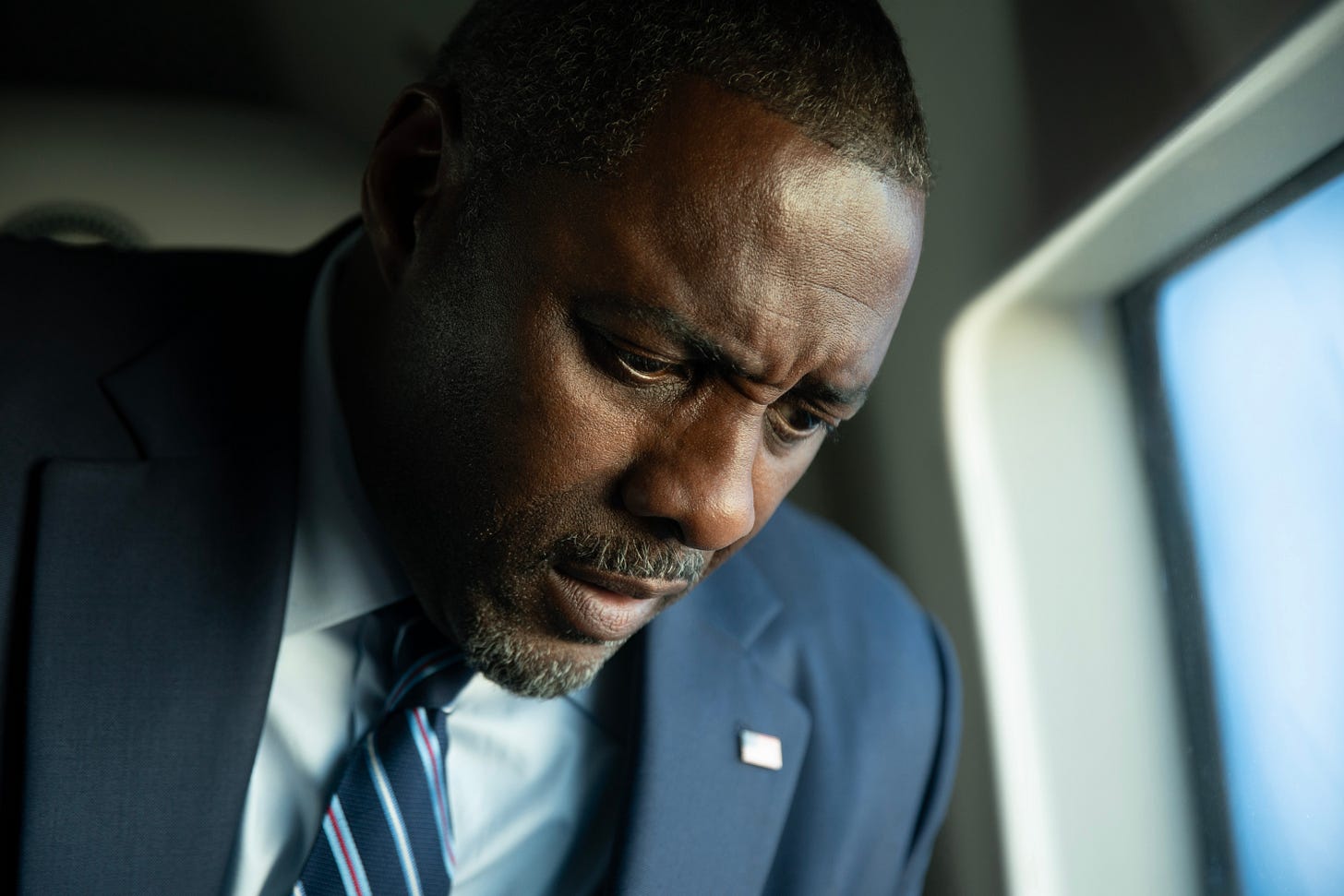

With unimaginable horror sinking in, Mission: Impossible star Rebecca Ferguson’s Captain Olivia Walker becomes one of the most impactful figures we cling to. Stationed in the White House Situation Room, she’s forced to assemble the Zoom of doom with every high-ranking official, including as-yet-unseen but heard POTUS (Idris Elba). But her phone is under lock and key as her oblivious husband manages with their sick kid.

With less than 20 minutes to act and the nation’s enemies and allies alike scrambling, the only window to stop the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) – billions of defence capability resting on a 50/50 shot, like trying to hit a bullet with a bullet – fails.

“There’s no plan B,” says Jason Clarke’s Admiral Mark Miller as he’s evacuated, leaving Walker to her fate, should DC be next, clasping the hand of her colleague, Malachi Beasley’s SCPO William Davis, who was about to propose to his partner.

At least Walker has time to grab her phone and plead with her hubby to flee west; national security is a moot point by this stage. Elsewhere in the White House, one of A House of Dynamite’s most quietly tragic moments occurs as we watch Willa Fitzgerald’s aide, Abby Jansing, not high enough up to be in the know, nevertheless knows what’s going down as armoured cops burst into the briefing room.

But it’s Foundation star Jared Harris who elicits the sharpest gasp as Pentagon-based Secretary of Defence Reid Baker says goodbye to his estranged daughter (Kaitlyn Dever) with one last act of mercy that will surely shatter any beating heart.

Commander in grief

In those feverish final minutes, the president, flying blind, is whisked from a basketball court shoot-out with real-life player Angel Reese and high-school girls.

He must choose whether to wait and see, as urged by a caution-sounding, unexpectedly elevated Deputy National Security Advisor Jake Baerington (Gabriel Basso), dashing from his gridlocked car and pregnant wife while desperately seeking answers from the Russians. Or strike back immediately, as urged by Tracy Letts’ fuming general, Anthony Brady.

But against whom? North Korea? Russia? China? And how did they evade early detection?

Surrender or suicide? It’s a cruel twist of fate that Greta Lee’s North Korean expert at the National Security Agency, Ana Park, is attending a Civil War re-enactment at Gettysburg with her young son, all too believably huffy at being called on her day off, before realising the gravity of what’s at stake for the nation.

Something our unnamed president must wrestle with, even as fraying communications leave him losing touch with the shocked First Lady (Renée Elise Goldsberry), thankfully far from harm on safari in Kenya.

None of these moments of desperate connection is played mawkishly. Bigelow’s furiously racing freight train never stops for sentimentality, nor does Volker Bertelmann’s dread-filled score.

An astoundingly sure hand, Bigelow has never flinched from wrangling with the imperial US’s snarling weeds in exceedingly prescient ways. Both sprawling and astonishingly focused, A House of Dynamite explodes off the screen, joining Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another as one of the year’s most exhilarating thrillers.

It feels unbearably truthful that, when faced with a black binder of worst-case scenarios lugged around up until now uneventfully by I Know What You Did Last Summer star Jonah Hauer-King’s blushing military aide, Lieutenant Commander Robert Reeve, Elba’s POTUS admits he doesn’t know what to do.

How could he? What would any of us do in these final hours?

Elsewhere

I chat to star Mark Coles Smith and director Kiah Roache-Turner about shark attack movie Beast of War for the ABC. I also spoke to Robert Carlyle about The Hack.

Over at ScreenHub, I interview Australian New Wave hero Bruce Beresford about his illustrious career and new film, The Travellers.

Over at Flicks, I reviewed Aisha Dee’s stalker-driven thriller Watching You. And here’s a guide to navigating the Adelaide Film Festival program.

At Melbourne Fringe, I review UK outfit Subject Object’s shows Work.txt and Instructions, plus Tom Ballard’s Jks: (a comedy?) Also in theatre, I took a look at MTC’s new adaptation of Rebecca and how Rent pays its dues to La Bohème.