Regular readers of Orion’s Shoulder will know my newsletter’s name springs forth from Ridley Scott’s neo-noir sci-fi masterpiece, Blade Runner, in which the appearance of a gleaming unicorn haunts the dreams of Deckard (Harison Ford). Now widely regarded as a cinematic triumph, the film was a box office disaster in 1982 after a long and difficult delivery. The unicorn vanished from the original cut.

Smarting from Blade Runner’s perceived failure – little knowing what the future would bring – Scott would return to an earlier idea. One that directly mined the trappings of fantasy and the iconography of unicorns as symbols of purity. Almost certainly my first watch from the great English director, Legend (1985) lit up my childhood with its visually resplendent battle between innocence and the Lord of Darkness (a horned Tim Curry).

A primal force of evil determined to damn the world to eternal night, Darkness dispatches a trio of goblins – Blix (Alice Playten), Blunder (Kiran Shah) and Pox (Peter O’Farrell) – to slaughter the unicorns that frolic in the forest near his blighted tower and bring their powerful horn to him. Lili (Mia Sara), the pure princess of countless fables, must enlist the support of her would-be-betrothed Jack in the Green (Tom Cruise), a relic of old folklore, to retrieve the horn and return balance to the world.

Majestic stuff, it cemented the unicorn’s place as an emblem of good in my young mind many moons before I contemplated what this image and its origami idol signalled about Deckard’s humanity. Later still, I would question why the unicorn depicting Scotland in the British coat of arms – displayed on every UK passport – is bound in chains. Putting aside my thoughts on the tragically failed independence bid for now, it’s fair to say I’ve been thinking about unicorns throughout my life, with great thanks to Scott.

Dead on arrival?

And so it was with great excitement that I cantered towards writer/director Alex Scharfman’s A24-championed Death of a Unicorn, despite rumbles of discontent emanating from the debut feature’s SXSW berth.

How could you possibly mess up a darkly comic movie that goes all in on the oft-overlooked mythological fact (I’m standing by this oxymoron) that unicorns are both mighty and mighty pissed if anyone other than a virginal maiden approaches them? Something the disgraced creator of Buffy the Vampire Slayer demonstrated with a snort-laugh-inducing death-by-goring scene in the otherwise uninteresting Cabin in the Woods. Alas, that’s exactly what Scharfman has achieved, and it’s a real bummer

Beetlejuice Beetlejuice actor Jenna Ortega once again adopts the stock-standard emo teen archetype the Wednesday star’s stuck in as Ridley (surely a nod to Scott?). She’s begrudgingly accompanying her father, Elliot (Paul Rudd), on a work trip. The bait? She gets to spend the weekend in the considerably-more-palatial-than-a-cabin, Canadian Rockies retreat of his filthy rich boss Odell (Richard E. Grant, way more entertainingly awful in the cruelly cancelled The Franchise).

She’s not much of a fan of Odell’s type and the way the mogul class whitewash their nefarious self-interest, sniping, “Philanthropy is just reputation laundering for the oligarchy,” at her dad when dad suggests the Sackler-adjacent Leopolds – including sneering wife Belinda (Téa Leoni) and gormless dudebro son Shepard (Will Poulter) – funnel a lot of money into good causes.

Ostensibly an eat-the-rich crucifixion in an animal rights mould, the twist comes in the opening moments when an alarmingly phone-distracted Elliot hits something heavy with their rental car before they reach the mansion. Something white as the driven snow and adorned with a horn. But faced with a hefty wildlife-slaughtering fine in a protected area, he decides to cudgel this injured creature he refuses to name even as Ripley is in cosmic communion with the beast, slinging its carcass in the boot.

Only it’s not quite dead, as soon becomes abundantly clear while Elliott’s trying to cross the Ts and dot the Is on a dying of cancer Odell’s will. Hold your bony protrusion horses; it turns out that unicorn blood not only dispels teenage acne – surely a strong business case there – but also turn back death’s ticking clock. But who’s hunting who when mum and dad descend, augured by the appearance of an aurora in the night sky?

It’s hard to care. The class clash suggested by the twin family dynamic never coalesces into anything particularly interesting. The Leopolds are too leaden to elicit the love-to-hate them energy of Succession, with their staff too thinly sketched to offer much on that front either, though Anthony Carrigan tries his best with little screen time as huffing butler Griff. An unusually lacklustre Rudd shares little chemistry or screentime with Ortega, the latter relegated to exposition dumping, throttling any potential panic when things get horny.

With Scharfman’s clunking screenplay neither as satirically witty nor as scary as it needs to be, Death of a Unicorn’s potential is fatally impaled by shockingly poor CGI where practical effects, as ever, would have vastly improved the unicorn rampage it takes way too long to get to despite clocking in at under two hours. Editor Rod Dulin needed to gouge his way through this far-from-magical affair with none of the spike required.

Where the wild things are

Wishing to wash away the bitter taste left by Death of a Unicorn, I sought out an intriguing alternative in Au Revoir, Les Enfants filmmaker Louis Malle’s beguiling Black Moon. A magnificently odd affair, this experimental 1975 fable, co-written by Joyce Buñuel and Ghislain Uhry, also begins with roadkill, but this time it’s a shuffling badger, rather than a unicorn.

The latter will appear, in somewhat strange circumstances, but not before a fascinating opening gambit in which Cathryn Harrison’s Lily, done up like a Fleet Street reporter in trench coat and trilby, careens through the countryside in her beat-up car, felling said badger. We come to realise she has adopted a then-masculine-coded look because there appears to be a gender war on in a dystopian world some ten years before Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.

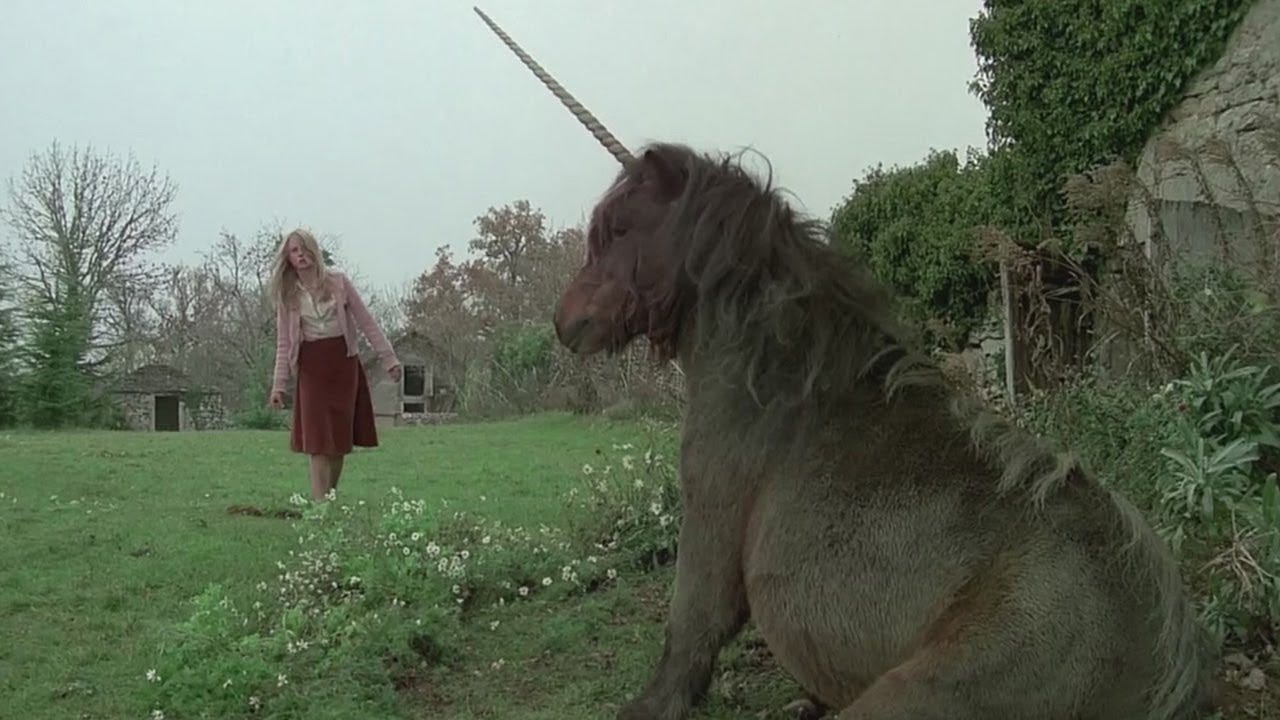

With her life at risk from machine-gun-toting men, with spectacularly staged slaughter on both sides of this divide, Lily soon abandons her drag and crashed car, instead rambling idyllic fields where the flowers squeal in pain under her feet. Here she encounters a rather plump brown talking unicorn who roasts her as “rather rude” for squishing the weeds even as it chows down on their distressed petals.

It’s not the strangest occurrence in Black Moon. There’s a dalliance with telepathic twins (After Blue star Alexandra Stewart and Warhol Factory-fired sex symbol Joe Dallesandro), both called Lily, and free-ranging feral kids. There’s also a bed-ridden crone (Mädchen in Uniform’s headmistress Thérèse Giehse) in a cluttered mansion given over to ripened pigs who hectors Lily prime, on her mentioning the unicorn, with this conflicting information, “Of course it doesn’t exist, and anyway, it’s a very insipid animal.”

Far from insipid, Malle’s lucid dream, shot by Ingmar Bergman’s regular cinematographer Sven Nykvist in half-light in and around Malle’s 200-year-old pile in the Dordogne valley, is an unforgettable vision that will stay with me way longer than Death of a Unicorn.

Elsewhere

My interview with The Narrow Road to the Deep North director Justin Kurzel in The Saturday Paper.

A chat with Amy director Asif Kapadia and investigative journalist Carole Cadwalladr about hybrid doco 2073 for the ABC.

Reviewing the opening episodes of The Handmaid’s Tale’s final season over at Screenhub.

A guide to the Steven Soderbergh movies screening at SBS on Demand.